It is that time of the year when I get a panic attack because I have not done the writing that I want to do and my ‘to-be read’ (TBR) pile is growing each week. Every book I turn to is engaging, I just want to hole up somewhere and read and read all day.

Time slips by when you read or think about things. In this digital age, time passes by quicker now that we have to perform tasks both physically and virtually. Time expands, time contracts depending on what we are doing. I wish time could slow down because I prefer to do things leisurely plus I need to conquer my ever growing TBR list.

During the week, amidst doing some work and trying to get the minimum seven hours of sleep, walking the dog that used to be my morning routine is no longer happening every day. I lose track of time when I scroll through emails and decluttering mailboxes for both work and personal but often end up reading the articles or essays. Then as I happen to delete photos to clear storage space on my devices, I end up scrutinising those photos and think about what happened when they were taken. It is that easy to get distracted. Meanwhile mind is 24/7, and there seems to be a zillion things on my mind. It is a good start of my day if I manage to put in fifteen to twenty minutes of some basic yoga stretches but that is not enough. As I move from one read to another, I am simply in awe of all these stories that are being told in different voices.

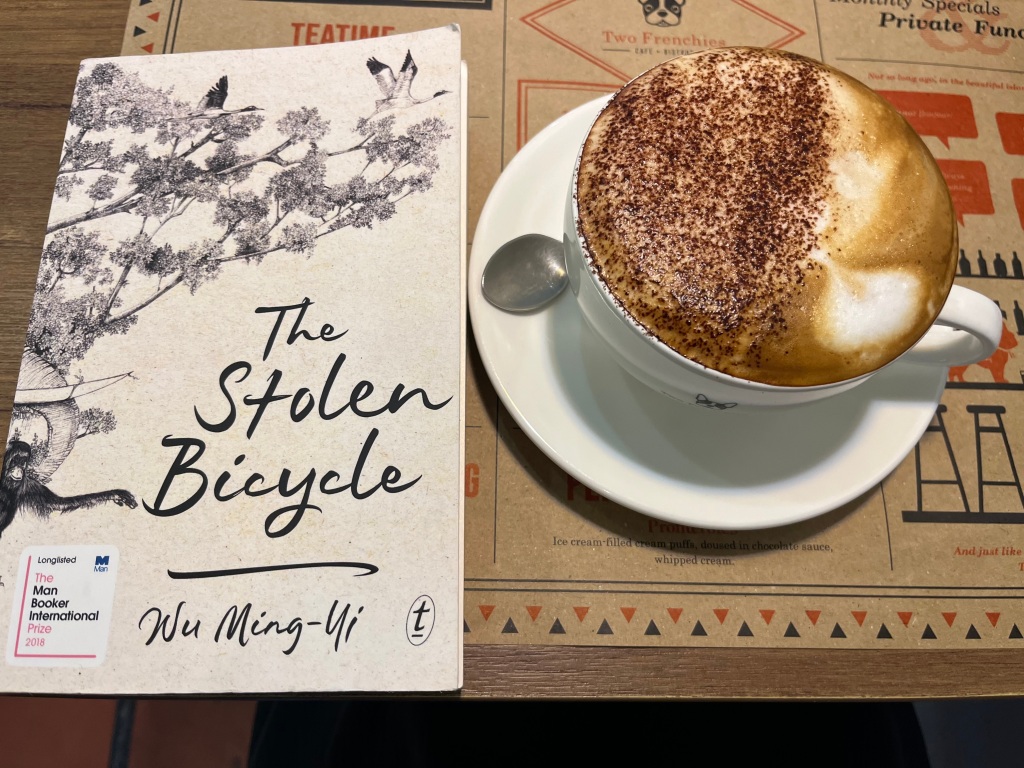

‘Stories exist in the moment when you have no way of knowing how you got from the past to the present. We never know at first why they continue to survive, as if in hibernation, despite the erosive power of time. But as you listen to them, you feel like they have been woken up, and end up breathing them in. Needle-like, they poke along your spine into your brain before stringing you, hot and cold, in the heart. ‘ – The Stolen Bicycle單車失竊記, Wu Ming Yi 吳明益.

The Stolen Bicycle was written by Wu Ming Yi in Mandarin Chinese and Taiwanese. Its English translation is by Darryl Sterk. The story is set in Taiwan. Ch’eng, a writer in his quest searching for his missing father’s stolen bicycle hopes to find his father who went missing twenty years ago. As he investigates and makes enquiries , he becomes closely acquainted with A-pu who is an antiques and memorabilia collector and dealer and Abbas, an aspiring war photographer. He finds himself caught up in the strangely intertwined stories of the soldiers who fought in the jungles of South-East Asia during World War II, the elephant Lin Wang formerly known as Ah Mei and the secret world of butterfly handicraft makers in Taiwan.

Bicycles play important roles in Ch’eng’s family history.For native speakers of Taiwanese, ‘Iron horse’ or ‘Kongming cart’ is the term for bicycle.The protagonist’s mother’s belief in the importance of bicycles has rubbed off him. In Cheng’s voice ,

‘What a beautiful term! ‘Iron horse’ includes the natural and the artificial.’

‘No matter how I tell it, this story has to start with bicycles. To be more precise, it has to start with stolen bicycles. ‘‘Iron horses’ have influenced the fate of our entire family,’ my mother used to say. I would describe my mother as a New Historicist: to her, there are no Great Men, no heroes, no bombing of Pearl Harbour. She only remembers seemingly trivial, but to her fateful- matters like bicycles going missing. The word for ‘fate’ in Mandarin is composed of two characters, ming and yün, each of which is independently meaningful. Ming means the life we are each allotted – our destiny – while yün means luck – the ups and downs of life, the twists and turns of fortune. Put the two characters together and you get 運, ming-yün, or like what I just said, ‘fate’ in Mandarin. But in my mother’s native tongue of Taiwanese, it‘s the other way around: 運命, ūn-miā, putting luck in front of life. ‘

In 1993, the market that Ch’eng’s family of nine lived in- and depended on for their livelihood was torn down in the name of urban development. That was the year his dad went missing. Years later, Ch’eng wrote a novel about a young Taiwanese man , one of more than eight thousand like him who had volunteered to go to Japan to work in a warplane foundry. After the war, the man returns to Taiwan, opens an electrical appliances store, gets married and has a son , but he never tells his son his wartime experience. At the end of the novel, the narrator’s father , Saburo rides his bicycle to Chung-shan Hall and then just disappears into thin air. Meme, one of Ch’eng’s readers has written to him and asked him “What happened to that bicycle?”

Ch’eng’s father ran a tailor’s shop and though the event is not fictitious, the rest of the story he had written was a work of fiction. That enquiry by Meme sets Ch’eng on a trail to look for the bicycle that went missing along with his dad. When his father went missing, he chanced upon a photo of three men and a boy standing in front of a cramped shoe store and one of the men stood astride a bicycle. It is both the photograph and Meme’s letter that started him on a quest to recover that Lucky bicycle in real life.

The Stolen Bicycle is full of fascinating tales such as the story told by Abbas about Old Man Tsou whom he met in 1992 when he was in the army , stationed in south-western Taiwan, in an anti-aircraft artillery unit at the air force academy there. After the war, Tsou lived alone and raised a bulbul that he claimed to house one of the Japanese soldier’s spirit. Abbas, an aspiring war photojournalist shows Ch’eng photographs taken from his cycling trips to shoot pictures from southern Thailand to Malay Peninsula following the route taken by the Japanese during WWII. His father, Pasuya was also one of the volunteers recruited by the Japanese in 1942 and he shares with Ch’eng recordings from Pasuya recounting his exploits with the Japanese army in South East Asia.

Ch’eng was born when his parents were in their forties. His mother had given birth to four daughters in a row and that made his dad despair even more than poverty. They kept trying and finally his Ma gave birth to his elder brother after his fifth sister, A-muá whose name means’ plenty’ as in ‘Enough, enough!’ One day, when his mother went to the market, his dad took A-muá with him as he had plans to take the first train to the countryside to pass her to their barren aunt. His mother arrived home and noticed that A-muá was not home. She rode the iron horse through the Chung-Hwa market and arrived at the train station, pushing through the hordes of desperate ticket-buyers to ask when the early train might be. Her husband saw her , he was initially shocked , then shamed and finally enraged. The incident is a testament to his mother’s love for her children and also to illustrate how poor they were. Ch’eng is considered lucky amongst the siblings as he did not have to endure the dire poverty his siblings had known but Ch’eng feels left out hence as an adult he has found a way to be part of those times – to grow up alongside his siblings , or even his mother by listening to their stories and re-creating ‘the good old days’ in words.

Their mother has had a fall and she is now in the hospital. Ch’eng goes to the hospital.

‘Ma was asleep from the medicine. I thought of the dismal uterus inside her withered body, which had given life and birth to seven children. Her present pain must be the after-effect of having given too much of herself to us. I drew the cubicle curtain, sat at a desk only sixty centimetres across and carried on editing the transcript of the second cassette, Forests of Northern Burma, that I’d patched together from Ning’s translations and the notes I’d made up in the mountains in Chiu-mei.‘

The novel is complex. It is an intimate meditation on memory, family, home and fate. It is a poignant tale about human sufferings during and after the war. In his postscript entitled: A Time Beyond Mourning, Wu explained that he did not write this novel out of nostalgia but out of respect for an era he did not experience, and reverence for the unrepeatability of life.

Here is a little description about Penang Island during WWII.

‘Penang Island, just off the coast, suffered heavy bombardment, and defensive preparations had proceeded too slowly to protect the power and water supply. Unable to hold the Muda, the 11th Division retreated another fifty kilometres south to the Krian. The Japanese army entered Penang’s capital, George Town, without firing a single shot. Shops stayed open for a new clientele : the Japanese soldiers who were eating ice-cream and shouting banzai!‘

My late dad used to tell me about how he sold cigarettes to the Japanese soldier. I imagine he was street peddling. I think that is what I understood when he told me but I cannot verify now. If only I had taken more interest in his stories. I have too many questions now that he has passed.

‘Through a quest for a bicycle that ends up involving the history of an epoch, the reader, I hope, might sense what the characters in the novel are feeling, the pulse of their pedalling and their different rhythms of breathing, the pulse of their pedalling and their different rhythms of breathing, and their sweat and their sadness – with or without tears. And maybe they will feel yours.’ – The Stolen Bicycle, Wu Ming -Yi [Postscript: A Time Beyond Mourning @page 371].

The author himself has become a collector of bicycles as he goes online to explore the history of Taiwan’s bicycle industry. In his words, ‘but with some things you can’t get a feel for it until literally hold it in your hand.’

Wu Ming-Yi is also an artist , designer, photographer, literary professor and an environmental activist. His novels have been translated into English, French, Turkish, Japanese, Korean, Czech and Indonesian.

Travel Note : Amazing landscape and views up and down the Taroko gorge carved by Liwu River at Taroko National Park, Hualien County, located in Xiulin Township, Taichung municipality.

2 thoughts on “In Search of the Past”